HueArts NYS Brown Paper

Findings

Funding & Finance

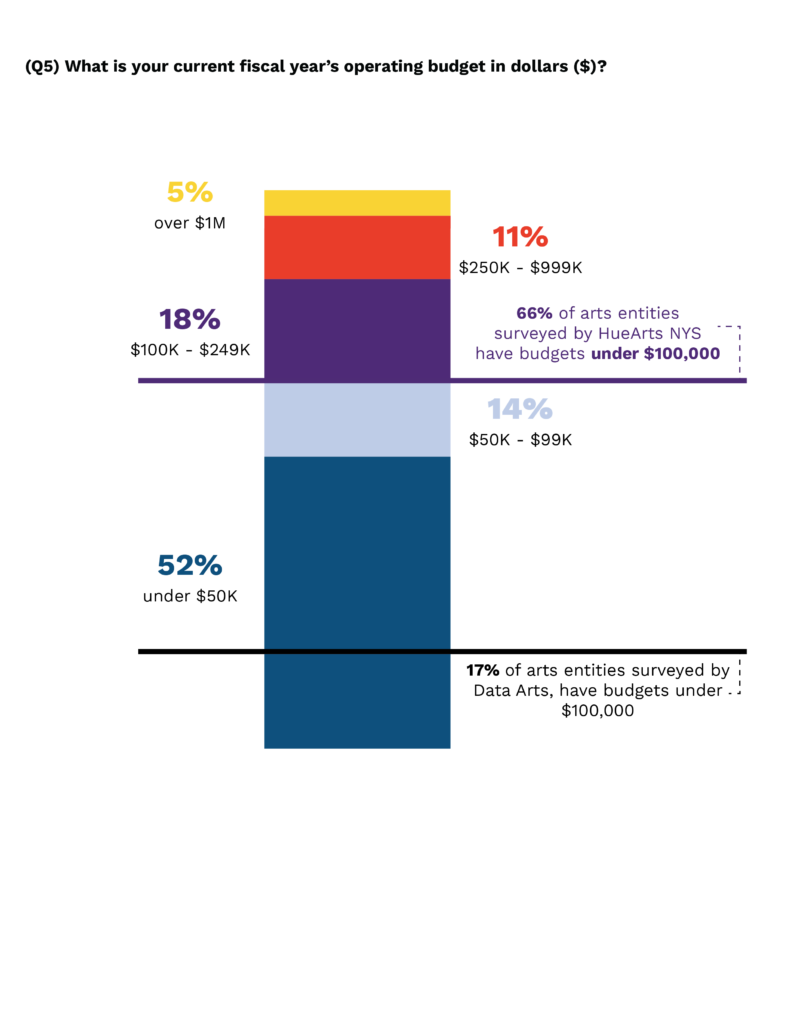

One notable finding that either directly or indirectly relates to every single theme – particularly funding/finance and staffing/capacity – is the budget size of the entities surveyed. Two-thirds (66%) have budgets of under $100,000. As a point of comparison, only 17% of New York State entities reporting to Data Arts (the primary entity collecting data on arts and cultural non-profit organizations nationwide) report budgets under $100,000.

Furthermore, more than half (52%) of the entities surveyed for HueArts NYS operate on budgets of under $50,000 (this is half the size of the smallest budget category surveyed for Data Arts). Because budget size affects every aspect of an organization’s capacity – how many staff members can be hired, what programs can be produced, what kind of space can be accessed, how much risk and/or financial adversity can be absorbed, how much administrative time is available – it is well worth keeping this extraordinary disparity in mind during review of every finding and recommendation.

Accessing funding is a primary concern for arts and cultural entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color. Although this is probably the case for most arts entities serving any population, for the organizations we surveyed, an unequal playing field greatly compounds the challenges of an already-competitive process. The arts, cultural, and historical leaders we spoke to described facing both explicit and implicit barriers to funding.

Fig 1: Stacked bar chart displaying the percentages of surveyed arts entities whose current fiscal year operating budgets in dollars ($) fall within specific bands.

Juror Bias and Lack of Representation on Grantmaking Panels

During our conversations, we heard that Black, Indigenous, and all People of Color are underrepresented on grant decision-making bodies. Reviewers often do not have the cultural context, background, or nuanced understanding of each applicants’ work to effectively judge the programs or work done by these arts entities, particularly when organizations are showcasing work, culture, and history that is not well known to the mainstream.

Additionally, when arts leaders of color are in fact called on to serve on grantmaking panels, these efforts fall short if work is not done to create a true culture of belonging where people are genuinely connected and new perspectives are truly valued. As it currently stands, panelists of color frequently serve in isolation, and are often put in the position of doing the additional labor of calling out inherent bias, providing ad hoc education, and fighting for equity.

As Cjala Surratt, co-founder of Syracuse’s Black Artist Collective, stated: “What is the compensation for the non-program-related labor of educating the partner and making sure communities are not tokenized or harmed? What is the impact on the organization that is doing the heavy lift on educating the partner?”

“Because Black, Indigenous, Latine and all People of Color have not had equal access to funding, spaces and training, it’s important for policymakers to level the playing field … funders should include leaders in the arts and cultural field on their boards and listen to them. Citizens in their communities should demand inclusion of People of Color from the policy makers and the funders.”

—Jackie Madison, North Country Underground Railroad Historical Association

Funder Priorities and Metrics of Worth/Success

We heard frequently that many common metrics of success and impact measurement are not aligned with the goals of arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color. Funders were described as expecting grants to be written with certain buzzwords and academic writing styles, rejecting other forms of writing or those with different backgrounds in the arts. One participant shared that their organization’s background in establishing a theater was discounted as “experience” because the theater had been in Puerto Rico.

In addition, organizations with small budgets sizes may be excluded from particular opportunities because their capacity to steward large grants is questioned. But this can be a catch-22; capacity relies on staff size. A lack of adequate staffing is a symptom of inadequate funding, not a measure of competence. But it is endemic to use budget size as an indicator of success, a measure of capability, and therefore a qualification for significant funding. However, if your organization is the only entity in the world promoting or preserving an invaluable local history that is largely unknown or misunderstood (as in the case of the North Country Underground Railroad Historical Association or the Seneca Iroquois National Museum, among others), can that value be measured in budget size? Such undertold narratives are of deep, consequential meaning to both past and living individuals, and to a true representation of our history at large. Without the work of these organizations, those histories are in genuine danger of being permanently lost. We lack metrics that adequately account for that value.

“I view our museum as an excellent resource for the history of the Underground Railroad, as it was not information that was readily known in the community. It’s not just freedom seekers that came through that route. We’re also talking about the Chinese because of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Vietnam draftees that use the same route. And today, we have immigrants going through. That’s not information many individuals are aware of in the US, and even in our community… Funders tend to not recognize our work because it was not well known.”

—Jackie Madison, North Country Underground Railroad Historical Association

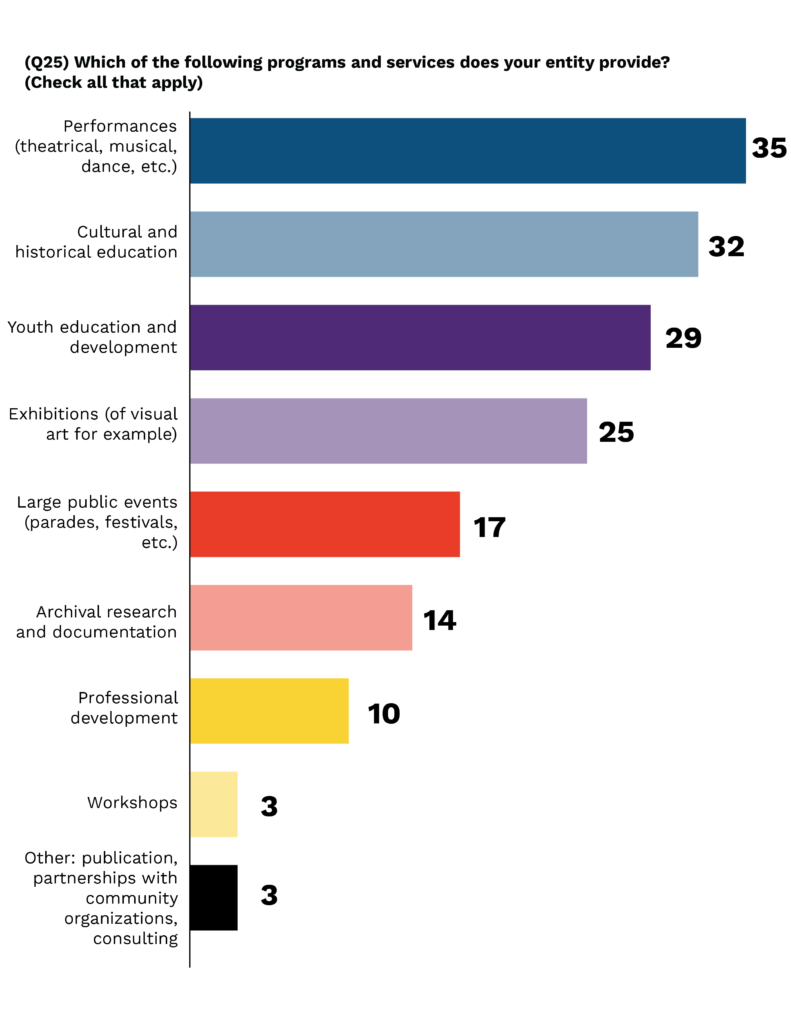

Overall, arts entities want rubric language for their communities that is rooted in the actual significance of their work. (See the “Recognizing Value” theme below, for more). It is also common for these organizations to provide services that benefit the community, such as youth development, elder engagement, or professional development, in addition to or as part of their arts programming. This ability for the arts to improve the quality of life, every day, is often invisible and not acknowledged as a measure of success or impact along with the usual metrics such as budget size.

On the flip side, because of the broad and diverse programming many of these arts entities provide, some have found success seeking money allocated for transportation or housing to create arts spaces. One of the Town Hall participants shared, “[Our] neighborhood wanted to expand the street – we diverted money to create arts spaces and became a neighborhood of the arts in Rochester. We went after transportation and housing money…How else can our communities be lifted up by the arts and get funding from organizations building community?”

“When we talk about what wraparound support organizations are able to provide at the community level, there’s nowhere on the application forms to add that information. It’s not valued in that sort of way. “

—Zainab Saleh, Squeaky Wheel / Frontline Arts Buffalo

“The other thing that’s undervalued, especially in our region with the work that we do as an organization, is that we’ve started workforce development for older people. We have our critical core group that we’re always working with – high school age – but now we started all these programs. How do we think about the value of arts institutions as providing stable income, jobs, and opportunities for people to live and thrive in their own communities rather than feel like they can’t survive in upstate NY as an artist? … Arts institutions can be a center of gravity and a grounding force to create a sense of sustainability and possibility in an upstate community that maybe didn’t exist before.”

—Bhawin Suchak, Youth FX

Eligibility and Application Processes

Within the existing funding models for grants, competition is fierce and applications are difficult. Many leaders expressed reluctance to participate in grant application processes because of the time and effort; small organizations cannot afford the administrative time if it repeatedly does not pay off, and they already feel they can’t compete with larger, more monied arts entities.

Some arts entities are ineligible for significant pots of funding because they are not located in areas slated to receive development funding (in some contexts, these are referred to as “opportunity zones,” often sites of displacement and gentrification). In other instances, arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color are located in geographies that aren’t very diverse, such as the Hamptons, which excludes them from certain funding initiatives.

In addition, funders may unexpectedly change their priorities or restrict the purpose for a grant, which can be disastrous for an understaffed small organization, particularly if they have already put significant time and effort into an opportunity.

Zainab Saleh of Squeaky Wheel/Frontline Arts Buffalo expressed frustration around spending a whole year advocating for federal ARP funds, only to find that the city re-allocated those funds, intended as capacity-building grants for small arts organizations – for larger organizations capable of absorbing a $250K project-restricted grant. “I’m feeling very disheartened this month..How do you convince [funders] to give us authority in an environment and be able to speak for ourselves?”

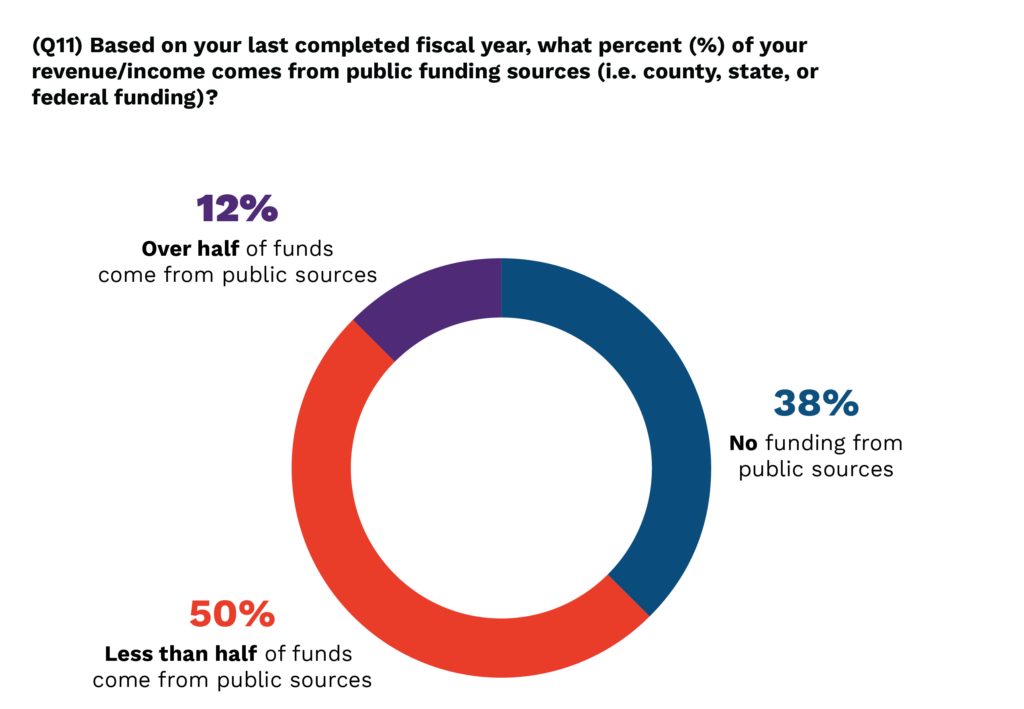

Many spoke of having difficulty accessing public funding; 37.5% of those surveyed had never received any federal, state, or municipal grants, in part because of onerous application processes that are particularly taxing on entities with limited staff (sometimes prohibitively so). As one arts leader noted, many people within these communities are taxpayers, so the awarding of public funds should be accessible to the arts entities that represent them.

New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) funding was described as notoriously difficult (their online system and lengthy application process in particular). One entity which was receiving professional grant-writing support recalled that even their grant writer struggled with Grants Gateway, an online portal used to submit NYSCA applications. Upcoming changes to the portal process are also frustrating for arts entities, who will now need to spend time and resources learning a different process.

“I worked for an arts council that awarded grants through NYSCA and many artists’ responses to funding barriers was the time it took to fill out the forms, coupled with the information requested and how it was not worth it for the grant amount they were applying for and the extensive reporting required afterwards.”

—Sylvia Diaz, Art JuXtapose Gallery

The usual process of applying for grant funding – particularly from public funding sources – was described as onerous, misaligned with the organizations’ actual work, and restrictive in its requirements. Consequently, for a notable number of the leaders we spoke to, it isn’t even part of their organization’s income equation.

Since grant funding is a huge source of support within the entire non-profit sector, and almost all non-profit organizations rely on it to some degree, this situation is a heavy blow to thriveability.

Tourism Funds

Tourism funding, which is also generated from taxpayer dollars, was specifically called out by several leaders. These funds have a designation for the arts sector to invest in marketing, infrastructure, and other projects to rejuvenate leisure, business, and travel in the area. They are public funds that benefit from the work of arts organizations through program visitation that creates income for local restaurants, hotels, and transportation.

However, tourism guidelines can disadvantage arts and culture entities founded, led by, and centering Black, Latine, Indigenous, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color, who frequently do not qualify even to apply for those funds. As noted, many operate on extremely small organizational budgets, and this budget range is frequently not eligible for tourism money.

Additionally, the nature of these arts entities’ work is often to simultaneously serve as community advocates and to address community needs. Funding requirements tied to generating tourism dollars are not only labor intensive (particularly challenging with a small staff), but are misaligned with these community-oriented goals and practices. If large funding pools for the arts are bound to tourism dollars, it effectively excludes the vast majority of POC arts and culture entities from even applying.

“Something must be done about that tourism (model) because we, the smaller organizations, can’t compete with the models that they have put forward … Before I Love NY, there was another campaign that we always refer to as a marketing scheme. It was those blue signs that certain museums got that can direct you off the Parkway or on major roads … We didn’t get access to those signs. But it goes back to the fact of staffing again, because the [requirement] to get into that program was you had to be open five days.”

—Dr. Georgette Grier-Key, Eastville Historical Society

Local/City Arts Councils

In addition to state funding, local arts councils are powerful institutions in the arts and culture industry in New York State. The leaders we spoke to came from an array of vastly different municipalities, and their experience of local arts councils was widely divergent. In some cases the power held by members of these arts councils was described as benefiting the few, or being used to provide programming for primarily white audiences.

“In the case of Teatro Yerbabruja, our organization was created to do theater. Today it is multidisciplinary, including visual arts, festivals, stalls. This was not the vision at first, but the reality is that the Latine artistic community has come to us with a need. One of the big challenges in Long Island is that there are too many Art Councils [that] only focus on their [own] programs and not on services to BIPOC artists. We [essentially] function as an arts council offering support services to Latine artists and artistic opportunities, although it is not part of our mission. Right now we have to rethink who we are and how to sustain the organization with so many artistic needs and few financial resources.”

—Margarita Espada, Teatro Yerbabruja

Some arts councils prioritize the goal of increasing tourism, which as described above can disadvantage or exclude small arts entities, and can be seen as a mission conflict for community-serving arts organizations. Similar to comments we heard about grantmakers in general, some councils were described as having few or no BIPOC grant reviewers, and grant processes that require excessive paperwork..

However, in other instances, some leaders we spoke with had very favorable experiences with their city arts councils. Municipal councils that have stronger ties to local arts entities build a deeper understanding of an organization’s programming, which can, in turn, lessen the burden of grant application processes.

When the local arts council folded in one community, BIPOC arts leaders responded by rebuilding it with a focus on BIPOC arts entities. Arts entities founded, led by, and centering Black, Latine, Indigenous, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color may also end up serving their constituents as an unofficial arts council in order to meet their communities’ needs.

Seeking Unrestricted Funds

Unrestricted grant funding that can be used for operations is of critical importance to POC arts leaders. As it is now, most grant support is restricted and can only be used to support particular events or programs. In order for arts entities to thrive and continue to provide programming, they need to be able to hire and support staff. Without it, they cannot always keep up with the program demands that restricted grants require.

“Funders seem to assume [all] nonprofits just have endowments or major donors to cover the ‘work’ and operational costs, and that all we need is programming funding.”

—Jeremy Dennis, Ma’s House

Some entities were able to receive money through the CARES Act and other COVID programs, which for many were more straightforward than most existing grant application processes, and more frequently provided unrestricted funds. However, this much-needed funding arose from extraordinary circumstances, and is not sustainable. These one or two- time opportunities have now evaporated.

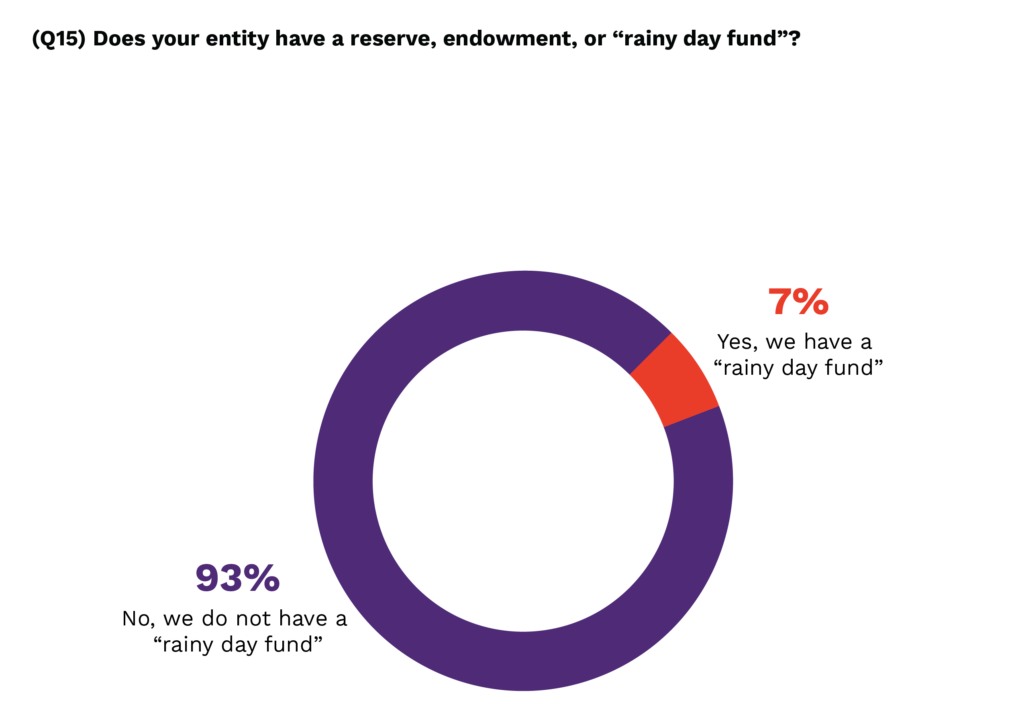

When they do receive grant funding, due to the long lead times imposed by application processes and the practice of government grants being issued as reimbursals (for which arts entities need to front the funds), arts entities often provide programming before they receive awards and then scramble to catch up – a particular hardship for organizations with small staffs and/or small budgets, usually (93.3%) operating with zero “rainy day” or reserve funds. Arts leaders spoke of the need to build up funding sources beyond public grants in order to grow sustainable funding. As one participant put it, “[restricted government] grants aren’t the answer to long-term sustainability!”

POC-led organizations can’t rely on funders who have traditionally excluded them, so several leaders recommended diversifying funding streams and seeking individual support. However, many of these arts leaders pointed out that the communities they come from may not have the resources to support them financially. Leaders in those communities largely lack opportunities to build assets…and flexibility. Consequently, they do not have access to a major “de facto” source that, in wealthier communities, serves to build organizational viability and artist livelihood.

If there is to be more equity in producing artwork and sustaining culture, it is imperative that the right plans and tools for financial management are put in place to facilitate long term staff capacity building efforts at arts entities founded and led by Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color.

Ma’s House, located on the Shinnecock Indian Nation adjacent to extreme wealth (including a “Billionaire’s Lane” once occupied by the Ko in Southampton) faces a different type of uphill struggle with raising funds from individuals:

“I’ve been invited to some of the Hamptons galas at different institutions. And you can just see firsthand how celebrity and wealth is used to a certain degree that you’re almost questioning like is this what nonprofits are supposed to do? … [For] smaller institutions where you’re just barely trying to pay your staff or even have staff, it’s just a huge disparity and very discouraging.”

—Jeremy Dennis, Ma’s House

Several leaders noted that there has been a shift in recent years in the attitudes of foundations and other funding institutions, and increased interest in supporting Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Access (DEIA) work.

While this is encouraging, there are varying levels of understanding about how to award this money effectively, and varying degrees of interest in ensuring that projects are led by and representative of the communities they engage. From a grant-seeking perspective, many POC arts leaders are struggling to find and connect with these funders.

Top photo: Frontline Arts Buffalo