HueArts NYS Brown Paper

Findings

Advocacy& Community Building

The Pre-existing Barrier: Silos

Collaboration and community are clearly valued by many of these organizations and leaders. But accessing and offering this solidarity presents its own challenges, and operating in isolation – in “silos” – is a big factor across Long Island, the Greater Hudson Valley, and all regions in New York State.

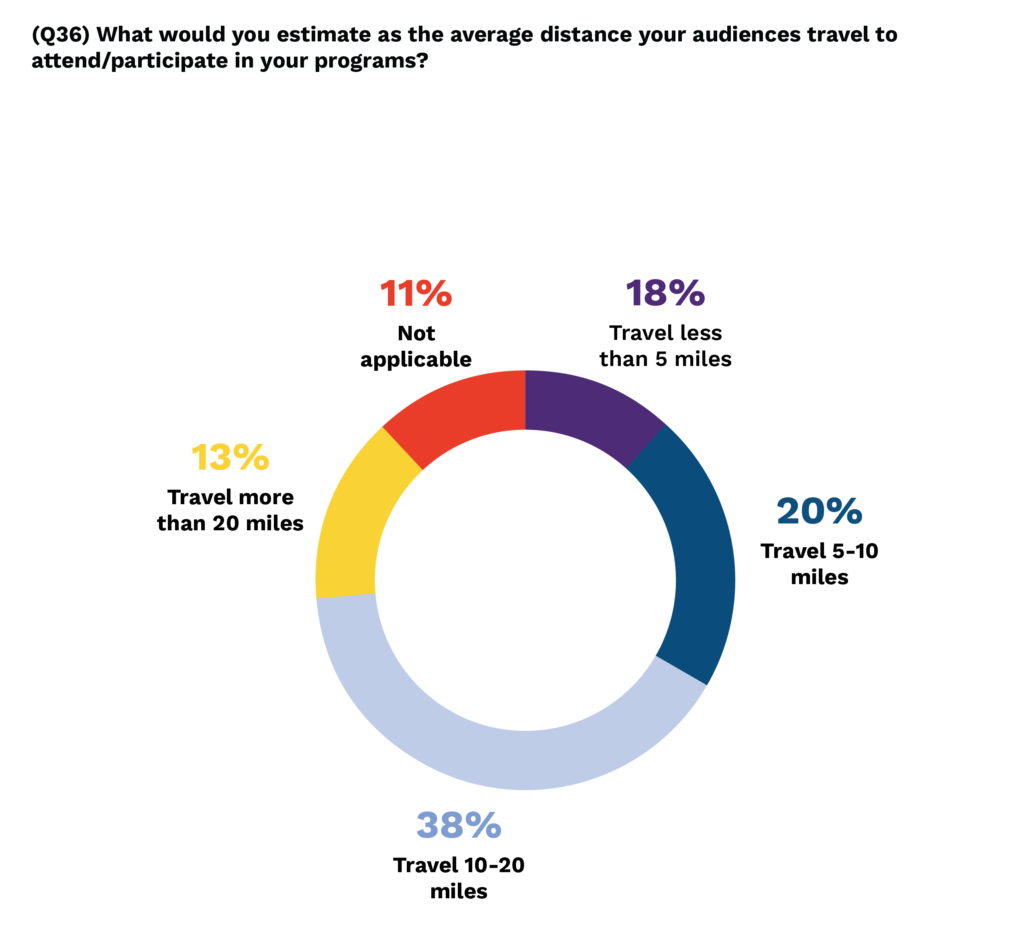

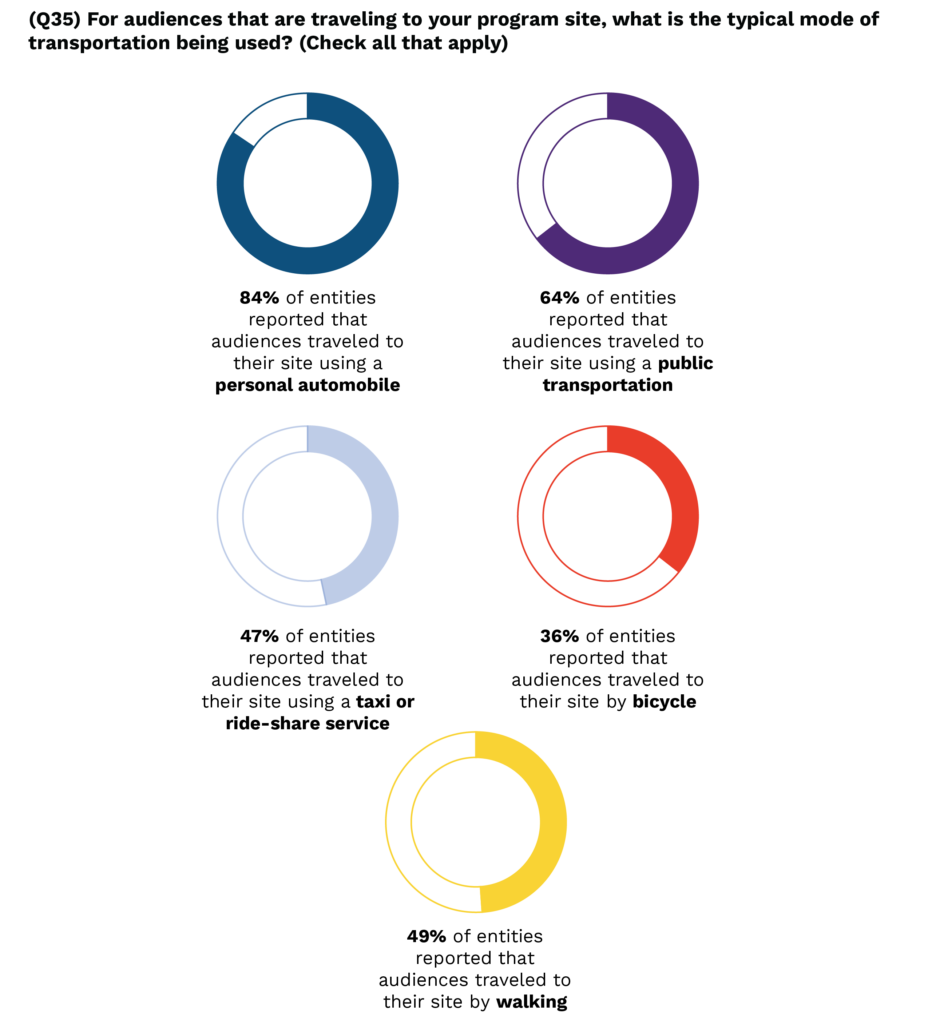

Each region has their own independent arts scene, often separated by many miles, and there is not much communication among them. There are often few options for transportation between geographically distant communities. Add this to the fact that, as noted above, it’s not uncommon for an area to have very few – or just one – BIPOC arts entity, and a sense emerges of how isolating the situation is for many of the arts leaders.

For a number of arts entities, one challenge that relates to siloing (as well as to funding and other important issues) is insufficient access to the technology infrastructure.

Many communities, especially those located in rural areas, lack basic internet access. Because the vast majority of funder information and application processes are now exclusively online, this makes even submitting an application for funding inaccessible; and it creates multiple challenges with visibility and community building, especially among different counties and regions.

“With so much information on the web and with art and cultural centers providing their materials in digital format, those areas without internet access will be left out of the loop. And, it’s not just internet access in rural areas because of the location, it is also limitations due to financial reasons. The latter tends to impact people of color the most.”

—Jaqueline Madison, North Country Underground Railroad Historical Association

In a state as large and varied as New York, lack of public transportation was frequently cited as a barrier to greater collaboration and interaction. Many of these arts and cultural entities are only accessible by car, and even if they are accessible by public transportation it can take considerable time to travel there from another area.

Policy Advocacy and Creating Change

Hand-in-hand with the interest of Black, Indigenous, Latine, Asian, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and all People of Color arts leaders to build community and strengthen collaboration is the desire for arts leaders to play a larger role in advocacy and policy-making: to have power within the arts and cultural industry in New York State. This includes having a voice at the governmental and policy level as well as serving on grant making bodies, as discussed in the Funding section. And as noted in both the Funding and Recognizing Value sections, many of the arts leaders we spoke to are already engaging in advocacy, in part because it is necessary for the survival of their organizations or their ability to conduct their programs and work.

“ [When we witnessed] that there were predatory permitting practices happening specifically to Black and Brown organizations looking to use our city and county parks, we sued the city and the police department and ultimately changed that permitting practice. So [for] something that actually has a legacy impact, you’re gonna have to make sure that it’s codified.

—Cjala Surratt, Black Artist Collective

… I’m proud of the work that we did for an entire year – and ultimately it means that those individuals who want to use the parks – our city parks that we paid for through our taxes – that now we can have dances, we can have theater events, we can have all these different kinds of celebratory events here, and if we choose to, we can opt out of having a police presence at those events.”

Despite the difficulty of advocating with limited access to allies and peers, and despite frequently operating as a sole staff person, handling multiple roles, and/or being volunteers, many take on advocacy work as a matter of course. This uncompensated labor is shouldered in addition to job descriptions that are already packed, often out of a sense of necessity and a deep commitment to community.

“Participating in legislative changes for artists statewide meant attending town halls and hosting meetings to gather people to rally them to participate. A lot of this work was done on my own, because it wasn’t something my employer would pay me [to do]. Even though this was essential to fulfilling my role, it didn’t fit the parameters for what they wanted to fund.”

—Sylvia Diaz, Art JuXtapose Gallery

“My recommendation would be [to have] a BIPOC Arts Council that has the funding sources just like the (NYSCA) decentralization grant that some of us may have received at one point, to be able to administer these funds … The only way I feel that we get it done is if we have our own council to deal with these issues and push us forward because there are such inequities … [that] have to be attacked on a regular basis. And so that means somebody needs to be in charge of making sure that our agenda is being pushed forward.”

—Dr. Georgette Grier-Key, Eastville Historical Society

The Importance of Coming Together

Fundamental to the ability to effectively advocate is the ability to increase communication both within and among different communities. The ability to advocate and to affect policy is closely related to the challenge of siloing – to ensure real traction for creating change, it is necessary to have the chance to explore commonalities and to act collectively in larger numbers.

“If you come inside the museum, the upper level exhibition is all about the history of barbershops and beauty parlors. Right away you see a beautiful mural in there – this mural was designed by David Martine from the local Shinnecock Indian Nation. We do a lot of collaboration there …

—Brenda Simmons, Southampton African American Museum

I’m thankful for Jeremy—we collaborate together and support each other, and that helps in the fight.”

“I think that in order to thrive as POC organizations, we really need to see each other as collaborative beacons rather than redundancies or competition.”

—Jeremy Dennis, Ma’s House

During our focus groups and town hall convenings, arts leaders stated that they didn’t realize many others were in the same position as them, encountering many of the same challenges. Prior to the HueArts engagements, most arts leaders felt like they did not have the opportunity to come together as a larger group, share resources, lift each other up, or learn about each other’s programming.

Bringing arts leaders together and asking them to share their struggles and successes made it clear that they were not alone in this work. They expressed deep interest in continuing to meet, and in harnessing these shared experiences to present a vision and strategy for their shared success. Fledgling entities in particular felt that they could benefit from more opportunities to meet with experienced leaders.

“I think one of the most incredible things about this evening, as a person that has been doing this work for nearly 35 or 40 years, is [that] the folks that were speaking were saying the things that need to be said, and normally there aren’t enough people in the room that know it, and can say it well … to sit here and be incredibly content with the fact that the folks that were talking had every angle covered. So thanks to everyone. Because, being a person of color in America is…tiring!”

—Sean McLeod, Kaleidoscope Dance Theatre Inc.

In an industry where allocation of resources often requires that these arts entities compete with one another, those we spoke with called for greater collaboration, cooperation, and solidarity to overcome their many shared challenges. Perhaps HueArts NYS will become the avenue through which these important conversations can continue, as a means by which POC arts entities can share resources, information, and support one another, and build collective power.

Top Photo: Black Artists Collective